Outliers

Red ink

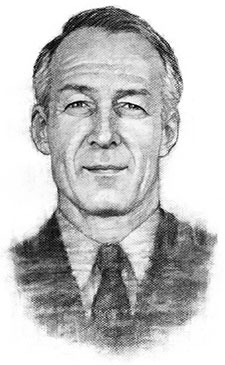

Alexander Saxton, failed novelist and unapologetic Communist, became an eminent historian of labor.

Carrie Golus, AB’91, AM’93

In 1938, Alexander Saxton, AB’40, dropped out of Harvard to work as a railroad laborer in Chicago. His dream was “to learn how people lived in the other America—the real America, as I thought, industrial America—and write about their lives.” The dean advised him to see a psychiatrist.

To appease his parents, Saxton enrolled in the College and completed his history degree. He also completed his first novel, Grand Crossing, published when he was 24.

If Saxton had not joined the Communist Party in 1941, his early promise as a writer might have been fulfilled. Instead, he spent two decades writing unpopular novels, completely out of step with Cold War sensibilities, while supporting his family as a construction carpenter. Saxton began graduate school at age 43 with the modest hope of teaching in one of the new community colleges. Instead he became a prominent historian of race and labor, producing two groundbreaking books, The Indispensable Enemy: Labor and the Anti-Chinese Movement in California (1971) and The Rise and Fall of the White Republic: Class Politics and Mass Culture in Nineteenth-Century America (1990).

It was an unlikely career for a child of privilege. Alexander Plaisted Saxton was born in 1919 to Eugene Saxton, an editor at Harper & Brothers, and his wife Martha, a literature teacher. In their Manhattan household, John Dos Passos, Thornton Wilder, and Aldous Huxley were frequent dinner guests. He attended Phillips Exeter Academy, then enrolled at Harvard in 1936; among his classmates was John F. Kennedy.

It was an unlikely career for a child of privilege. Alexander Plaisted Saxton was born in 1919 to Eugene Saxton, an editor at Harper & Brothers, and his wife Martha, a literature teacher. In their Manhattan household, John Dos Passos, Thornton Wilder, and Aldous Huxley were frequent dinner guests. He attended Phillips Exeter Academy, then enrolled at Harvard in 1936; among his classmates was John F. Kennedy.

But Saxton was part of a generation “radicalized by the Great Depression,” he wrote. Two childhood memories—seeing old women standing in a breadline in the winter cold and crowds of workers demonstrating at Union Square—had affected him powerfully. After quitting Harvard, he took a job repairing train engines, working six days a week for 25 cents an hour. “Coming from New York, a commercial city,” he wrote, “I was stunned by the beauty and horror of industrial Chicago.”

Saxton did well in the College, except for Cs in two English classes he took as a senior—the year he began his first novel. A year after graduating in 1940, he married classmate Gertrude Wright, AB’39, AM’41, a social-work student.

Grand Crossing, a semi-autobiographical novel about a Harvard student who transfers to UChicago and becomes a railroad switchman, was published by Harper & Brothers in 1943, while Saxton was serving in the merchant marine. “I recall it with special fondness,” he wrote decades later, “because it is the only book I ever wrote that earned any money.”

Saxton’s second novel, The Great Midland, featuring sympathetic protagonists who also happened to be Communists, came out in 1948. By this time, the Cold War had begun; the “embarrassed” publisher, Appleton-Century-Crofts, “tried to pretend it had never published it,” Saxton wrote. In 1951 he was summoned before the House Un-American Activities Committee, where he refused to testify. The government did not pursue him, but two job offers—scriptwriter at Paramount and creative-writing instructor at San Francisco State—quietly evaporated.

Saxton’s third and final novel, Bright Web in the Darkness, about a white woman and a black woman who meet in a welding class during World War II, was published in 1958. The next year Saxton left the Communist Party but never apologized for joining: “Party membership cost me dearly in some ways,” he wrote. “It was also a privilege I would not wish to have missed.”

In 1962 he began graduate work in US history at the University of California, Berkeley. His dissertation on the exploitation of Chinese workers in the 19th century—revealing for the first time how organized labor profited from anti-Chinese sentiment—became The Indispensable Enemy, an influential work of race and labor history.

Saxton ended his career as a professor of history at UCLA, where he helped found its Asian American Studies Center. His most cited paper, “Blackface Minstrelsy and Jacksonian Ideology” (1975), is considered one of the early texts in black-history studies. In 1990 he published The Rise and Fall of the White Republic, which examined the centrality of racism in American politics and culture.

In his last years, Saxton, who had lost his wife and one of his two daughters, suffered from declining health. Last August, at age 93, he died of a self-inflicted gunshot wound at his home in Lone Pine, California. His surviving daughter, Catherine Steele, told the New York Times, “He felt the terms of his life were his to decide.”